This article was researched and written in early 2019. A shorter version was published in September 2019 in Mongabay, who originally commissioned the piece.

“Cherry, mango, star apple, pam, cashew, pomegranate,” Carol Dabie, 37, rattles off a list of trees that once filled her family’s yard. She recalls climbing them as a child, impatiently waiting for the small, round, sweet pam fruits with their shiny black skin to drop.

As in many backyards across Georgetown – Guyana’s expanding coastal capital – Dabie’s childhood trees were eventually cut down and the fertile earth entombed beneath concrete. It’s a shift reflected in the city’s architecture too, with breezy wooden structures slowly being replaced by low-maintenance concrete blocks.

A keen gardener, Dabie now makes do with garden pots to cultivate a host of herbs. She grows pepper, sweet pepper, fine and broadleaf thyme, and a variety of basil known locally as “married man pork.” Other ingredients come from the city’s bustling street markets.

Access to fresh, local ingredients is a necessity for Dabie’s food delivery venture, Carol’s Creole Cuisine. After nearly two decades working as a local TV producer, she established the company in early 2019.

Every weekday morning, she prepares huge pots of Guyanese favorites like split-pea cook-up with fried banga fish, chicken chowmein, and bunjal duck – slow cooked until the sauce has all but evaporated. Some days it’s seven curry: a dish customarily served at Hindu weddings and pujas (religious ceremonies).

As the sun rises, and the temperature with it, the food is transferred into plastic containers – ready to be delivered to customers around the city in time for lunch.

In Georgetown, and throughout Guyana, customs and rituals related to food are woven into daily life. Friends and neighbors, especially those living outside the city, exchange fresh produce from their bountiful backyards. A daily radio segment called “What’s in your pot?” invites listeners to call in and describe what’s cooking on their stove. Good hospitality usually involves delicious smells emanating from the kitchen, and a box to take home leftovers.

So perhaps it’s not surprising that scientists say they’ve discovered connections between Georgetown’s deep love of food and the city’s flora.

A recent survey found that a massive 73% of trees recorded in Georgetown were cultivated for their edible fruits. That survey forms the foundation of new paper “Colonial history impacts urban tree species distribution in a tropical city”, published in July 2019 by Urban Forestry & Urban Greening.

In total 1,156 trees were recorded, including 57 unique tree species. Of all those identified, 38% had their origins in Asia, 34% were pan-tropical species, while the rest came from the Americas (17 percent), Africa (6 percent) and Oceania (5 percent).

The researchers didn’t stop there. They then looked at the ethnic composition of each community they visited in search of correlations between the origin of the trees found and the ethnicity of people living nearby. For instance, were there more trees of Indian origin in predominantly Indo-Guyanese areas?

What they found wasn’t what they expected.

“Surprisingly, considering the presence of tree species with close links to Indian culture,” the authors conclude in the report, “we found that ethnic composition of neighborhoods had a minimal effect on tree species abundance.”

Their suggested explanation? Food. Or to be specific: Guyanese food is a “unifying national identifier across ethnicities.”

Just like Guyana’s cuisine, the city’s trees reflect the various cultures of the people who have made Guyana their home. That includes descendants of African slaves brought first by Dutch then British colonizers. The Indian indentured laborers came after emancipation in 1838 to work on the sugar-cane plantations. The smaller numbers of Chinese and Portuguese also came in search of work. Then of course, there are the indigenous Amerindians – the original guardians of the tropical forests that cover more than 87% of this South American country.

Despite such diversity and many mixed relationships, racial divisions do bubble up at times, particularly during general elections when Afro-Guyanese residents are pitted against their Indo-Guyanese neighbors.

But in the kitchens and backyards of Georgetown and throughout the country – with the Atlantic Ocean to the north, Suriname to the East, Brazil to the South and Venezuela to the West – food is the glue that unites this land of six peoples.

Cook-up, pepperpot and Guyana’s colonial roots

Guyanese talk with pride of their unique, blended cuisine. Every good cook in Georgetown is as adept at making cook-up (a mix of rice, meat and beans boiled in coconut milk) as curry and roti, chowmein, or the national dish, pepperpot – traditionally an indigenous stew made with cassareep (from cassava).

“I make all kinds of dishes but [have] never really categorized them as African, Indian and Chinese – just Creole,” Dabie said. She’s not the only one.

Food here, whether in backyards or restaurant kitchens, has helped forge a national identity. Thanks to the city’s trees and plants, different culinary traditions have survived, prospered and been passed on.

To find out what effect Guyana’s British colonial history has had on the trees found in Georgetown today, researchers compared their data to existing surveys from cities in neighboring Brazil and Venezuela, which were colonized by Portugal and Spain, respectively. They found 14 tree species unique to Georgetown, including the star apple (Chrysophyllum cainit), cotton tree (Bombax ceiba), ackee (Blighia sapida) and katahar (Artocarpus camansi).

The implication is that the unique species were brought to Guyana either by the British colonialists or by the people they transported here. It’s not surprising, then, that the majority of the trees in Georgetown come from Asia rather than Africa. Indian arrivals in Guyana came largely by choice, so would have been more likely and able to carry items of their choosing.

“The laborers would have carried seeds and cuttings with them of their favorite plants and herbs,” says Dr. Mark Tumbridge, a lecturer at the University of Guyana. “With a view to trying to get them to grow here in Guyana and elsewhere in the Caribbean.”

A trail of seeds

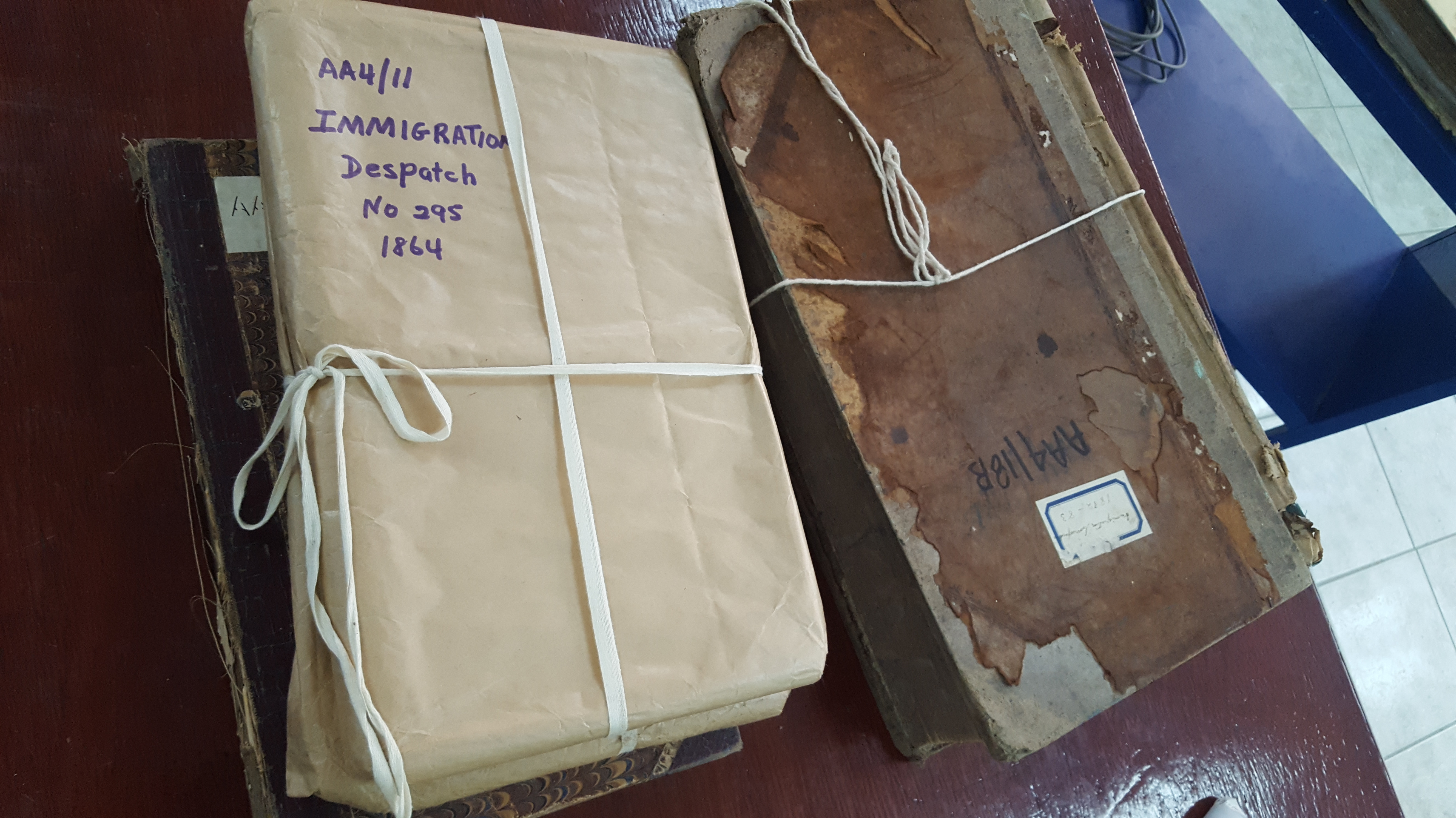

At the Walter Rodney National Archives in Georgetown (named for the famous Guyanese historian), archivist Karen Budhram helps me scour the British colonial government’s old dispatch notes in search of references to trees and seeds brought into what was then British Guiana.

We gingerly uwrap original record books, bound with creased brown paper and cotton string, and delicately turn the pages. Some of the fragile paper flakes off and blows away.

A cursory look doesn’t reveal records of what Indian laborers brought with them, but there are other clues.

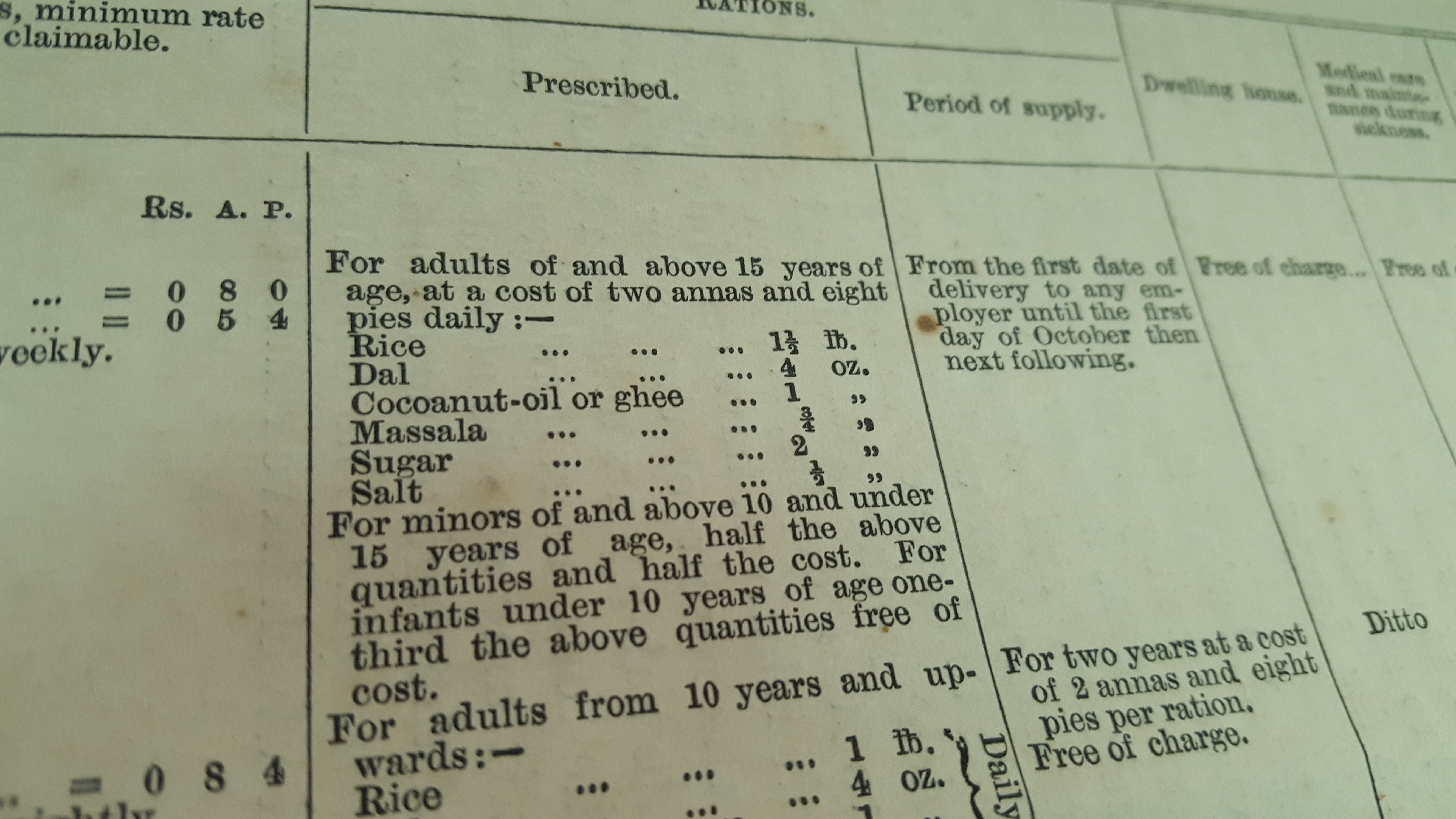

One is the list of rations given to adult laborers aged 15 and older: 4 chittacks of rice (a chittack is about 2 ounces in weight), 1.5 of dhal, half of coconut oil or ghee, one of sugar, 1.5 kanchas of masala, and “yams, plantains, sweet potatoes, tannia, cassava or corn meal 1 seer, or flour ½ seer.”

These were standard provisions for new arrivals to supplement with whatever they could cultivate on the parcel of land allotted to them.

Katahar, for example, is originally from Papua New Guinea. The report’s authors speculate that it most likely made its way to Guyana via India through indentured servants. Or perhaps it represents historical trade linkages that preceded colonialism. Alongside its role as an ingredient in seven curry, the katahar (or rather its dried flowers) are burned by some in Guyana to help keep mosquitoes at bay.

The ackee tree, meanwhile, was likely brought to the Caribbean from Ghana on a slave ship, according to the Jamaica Information Service. “Enslaved Africans were considered economic goods, therefore enslavers fed them on board ship and on the plantations to keep them alive and economically useful,” notes a document from the UK’s National History Museum entitled “Slavery and the Natural World.” This included importing foods such as breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis) and ackee “to feed enslaved people cheaply.”

Georgetown: the early days

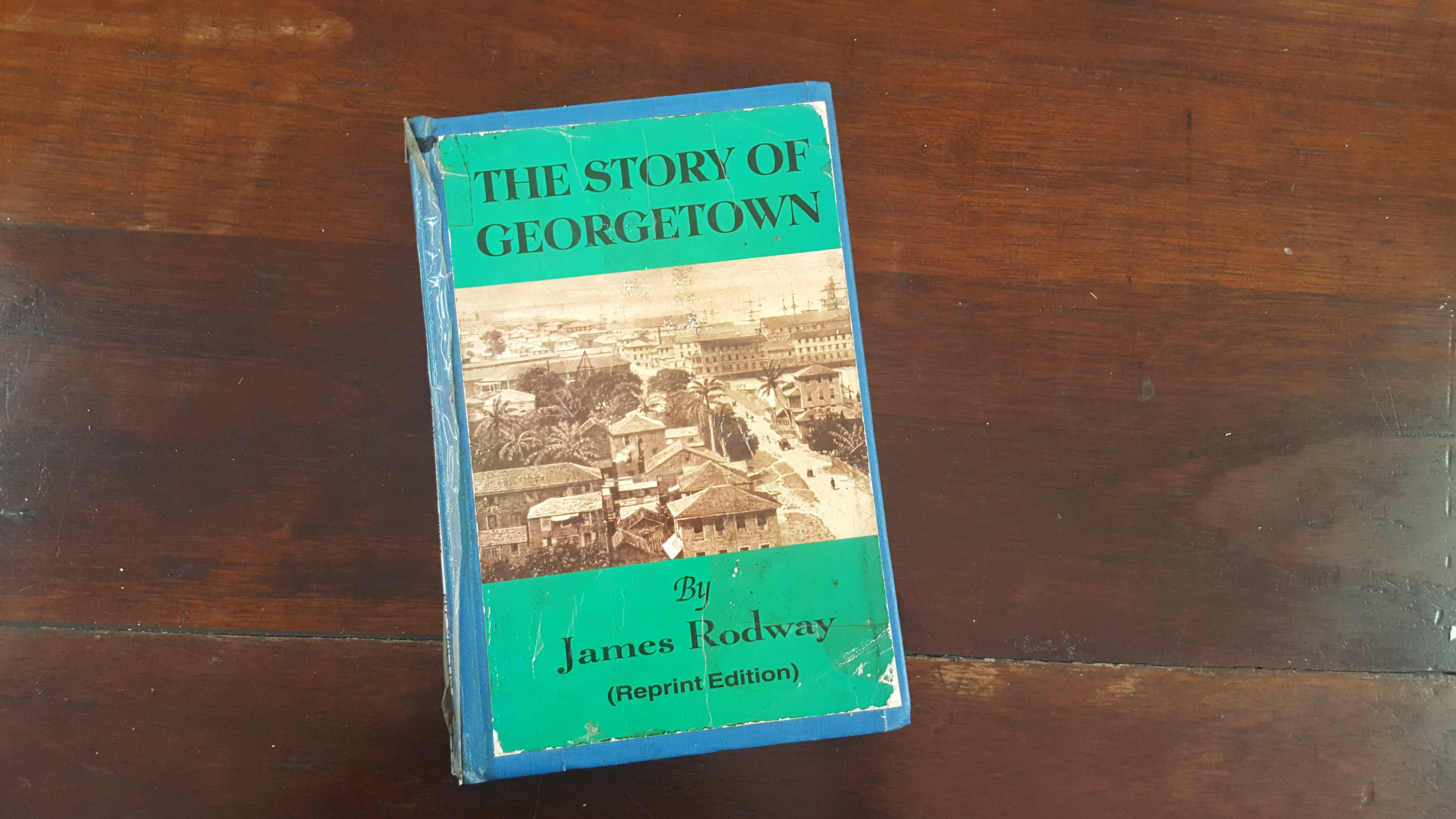

Tucked away in the small reference library upstairs at Guyana’s National Public Library is a copy of historian James Rodway’s book “The Story of Georgetown.” First published as a series of articles in the local Argosy newspaper in 1903, and then in 1920 as a book, it gives a fascinating account of the growth of Georgetown under British rule.

Particular attention is paid to planting trees and creating green spaces.

Describing one such exercise, Rodway wrote: “An early attempt to decorate Main Street was by a double line of Oleander [Nerium oleander] on either side of the canal, but these bushes never looked well. Every donkey boy seemed to find them convenient for switches, and the flowers, when they succeeded in coming out, were ruthlessly broken off.”

The creation of public gardens was heartily endorsed by Rodway. “We must thank the Botanic Gardens for almost everything we have today,” he wrote, noting the involvement of Mr J. F. Waby of Trinidad, who came to lay out the gardens. It was part of a series of British colonial gardens established under the auspices of Kew Gardens in London.

Georgetown’s coastline sits below sea level at high tide, so trenches were dug and land raised to drain the swampy soil.

“The nineteenth century emphasis was on economic botany, which meant colonial botany,” wrote Lucile H. Brockway in her 1979 journal article, “Science and Colonial Expansion: The Role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens.”

“Kew became a clearinghouse for the exchange of plant information and a depot for the interchange of plants throughout the empire,” Brockway wrote. “It sent plants wherever it saw commercial possibilities.”

In Guyana, the Botanical Gardens became not only rich in biodiversity, but something of a social destination too, with a band playing every Wednesday afternoon. The band is no more, but otherwise the garden’s role hasn’t changed much through today.

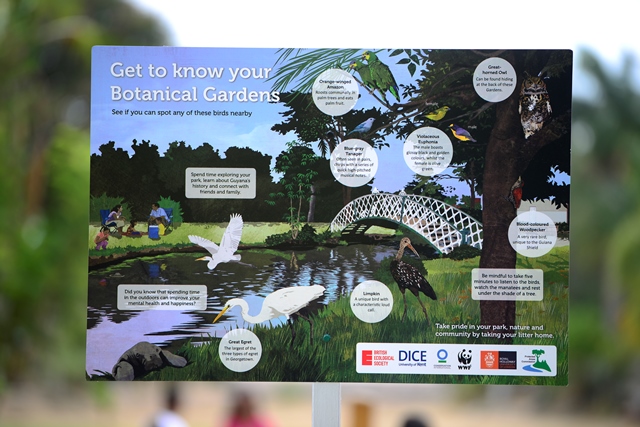

According to the Botanical Gardens’ current supervisor, Delroy Thomas, many people use the gardens to relax, unwind and escape the trials of everyday life. Others come to take their wedding photos or see some of the 185-plus species of birds. School groups often visit.

“The gardens have a lot of historical sights,” Thomas said from his onsite office. “The seven ponds, the mausoleum, the national heroes that are laid here, the iconic kissing bridge, [and] one of three bandstands.”

Historian Rodway recognized the health and safety benefits provided by trees in the city.

“Where houses are so close together that there are no gardens, diseases and fires can be rampant,” he wrote. “It is a curious fact that yellow fever has only once appeared since the great Water Street fire and never since tree planting became so common.” He noted that shade provided by trees can also help stop evaporation of water in the canals.

Georgetown’s urban forest has longstanding societal benefits, too.

Trees are often gathering points for villages and communities, particularly in countries with copious amounts of sunshine like Guyana.

“Under a tree near the Union Coffee Houses in America Street, the merchants of that time met and held a kind of exchange,” wrote Rodway. “Here were discussed subjects as narrow escapes from the enemy, prices of produce, rates of insurance, time of sailing of the next convoy and the latest news of the war.”

In the decades and centuries since, Georgetown’s trees have seen residents through many more tough times.

Seeds of discontent

In Guyana there’s an expression for when things are tough financially: people call it “hard guava season.” The implication is that times are so hard, you have to eat guavas (Psidium guajava) before they’re fully ripe. The fruit trees scattered across Georgetown have seen locals through some serious hard guava seasons when resources like food were scarce.

In “Guyana Diaries: Women’s Lives Across Difference,” for example, author Kimberly D. Nettles described the 1970s and 1980s as, “characterized by vast spending cuts that triggered widespread food shortages and the impending breakdown of the public and social service sectors.”

The president at the time, Forbes Burnham, banned the import of many food items – including canned goods and wheat flour – in an extreme bid for self-sustainability. Long queues became the norm outside government food stores and a black market for smuggling food flourished. Some housewives buried illicit flour in their backyards.

Many Guyanese migrated overseas, mostly to the UK, US and Canada, though some went to neighboring Venezuela – a dark mirror of what is happening at the border today, with Venezuelans now coming into Guyana in search of food and medicine.

Guyana’s fertile soil provides for its relatively small population, which numbers less than a million. Although more investment in agriculture is needed, Guyana is doing better than most countries in the Caribbean, which rely heavily on imports. It is one of just three CARICOM countries that produces more than 50% of its food consumption (the others are Belize and Haiti), according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Nevertheless, encouraging residents to maintain trees in their yards is crucial now that the population of Georgetown is growing and work patterns are changing. As new arrivals come from outside the city and the country, looking for jobs in the nascent oil and gas sector, Georgetown residents will be looking for economic stability.

“What are they going to do?” asked report lead author Nadia Hunte in an interview. “Cut down the little garden or space that they have with trees in their backyard and extend: build apartments to now accommodate this huge increase [of population].”

She laments that housing lots are being allocated and new sites developed without accompanying context about trees.

“They’re not telling the homeowners: ‘Leave this amount of space for plants’,” Hunte said, adding that she and her colleagues hope the report will help convince authorities to protect existing trees and plants, as well as plant new ones.

In his day, President Burnham was known to parade around the city on a horse, instructing residents from his high vantage point on the importance of planting their yards. Luckily, the report’s authors have some fresh ideas on educating the public.

For starters, Hunte is working on plans for a tree restoration project in Georgetown. “I’m working along with someone from the Ministry of Communities and I’ve also pitched the idea at the mayor to see if they could come on board,” she said.

According to Georgetown Mayor Ubraj Narine, the city council’s tree planting plans are already underway. “Yes,” Narine said in an interview. “We’re planning to restore some of the trees that probably died or [were] destroy[ed]. We plan to restore a few of them. And we’re planning to trim and neaten up some of them as well.”

Traditional healers

Maintaining Georgetown’s trees is also key given the importance still attached by many residents to herbal medicines, which rely on a ready supply of natural ingredients.

The Bakja Health Movement’s clinic sits in a shady, tree-filled yard a few miles outside of Georgetown. Inside, the facility is something of a rabbit’s warren of rooms that hint at what goes on here: steam room, prayer room, massage area, gym, kitchen, lab, classroom, conference room, enema washroom, computer room, psychotherapy room.

Little jars of remedies and tinctures sit alongside homemade teas, while one table display features carefully labeled tree branches – examples of those used by the center’s staff and students to make a number of their treatments. Some branches come from Georgetown, others are brought back from the interior of the country by obliging miners.

“This is not alternative medicine,” said Dr. Iamei Aowmathi, president of the Bakja Health Movement and the Guyana Association for Alternative Medicine Institute. “The alternative is what you use to the original, and this is the original. So alternative medicine is really the conventional.”

Aowmathi’s goal is to raise awareness of traditional and indigenous medicine – which is readily available and comparatively cheap. He noted the pharmaceutical industry similarities: “85% of their drugs are being manufactured with plants, herbs, trees, barks – the raw material comes from our environment…but we have to export the raw material and it’s being sent back to us chemically injected.”

In preparation for our interview he drew up a list of trees in Georgetown and some of their local medicinal values. For example, the banana tree (Mua sapientum), whose leaves can be used in a bath to treat shingles; in a tea for worms; or as poultices for burns. The fruit meanwhile is described as antifungal and antibacterial.

Another is the noni tree (Morinda citrofolia), which is said to be high in Vitamin C. Its leaves can be wrapped around rheumatic pains, according to Aowmathi’s list, while the fruit is good for diabetes and ulcers, as well as sore and inflamed areas.

The catalog of ailments is extensive – and, according to Aowmathi, not random at all. “In Guyana we have a problem with hypertension [and] diabetes,” he said. If you look at the trees, he explained, it’s obvious that whoever planted them had medicinal benefits in mind.

The Bakja Health Movement promotes what Aowmathi has named Caribbean African, Asian, Amerindian Indigenous Medicine (CAAAIM), which he hopes will one day be as recognized as Indian ayurvedic or Chinese traditional medicine, and encourage health tourism in the region. Despite drawing on herbal traditions from many cultures, the origins of the treatments he and his team make have blurred over time – just like the varied cultural inputs into Guyanese cuisine.

“It is so funny that in the plant world, there’s not Indian and African,” Aowmathi said. “There’s no discrimination among the plants. And there are no plants that tend to be wiser than the other plants!”

Trees are also known to play a critical role in mental health. Up until a few years ago, Guyana was frequently cited as the country with the highest suicide rate in the world. While it no longer holds that unfortunate moniker, efforts are being made to explore how green spaces – and blue spaces relating to water – can help improve the wellbeing of city residents.

Jess Fisher is a PhD researcher from the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE) at the University of Kent. She’s been looking at how Georgetown’s population perceives and values biodiversity in the city, and what it means for their mental wellbeing. “Many people living in the city have never been into the interior and their lives are dominated by urban experiences,” she wrote via email.

She visited Guyana in 2019 to support a project led by the Protected Areas Commission (in partnership with WWF Guianas and Conservation International Guyana) to understand how Georgetown’s residents perceive urban wildlife.

Over Easter they held an event in the Botanical Gardens to raise public awareness of what nature can be found in the city, with activities including a “self-guided wellbeing scavenger-hunt through an interactive app.”

They also established signs in the gardens about nature and wellbeing, and collaborated with local and international biologists including Will Hayes, Meshach Pierre, Arianne Harris and Courtney Hughes to create a bird book for school children. By gathering data on how people in Georgetown connect to their environment, they aimed to encourage residents to take responsibility for and re-engage with nature.

Biocultural connections

As well as being a way to improve green infrastructure and the quality of life in cities, looking at the biocultural significance of trees in a multi-ethnic city like Georgetown can help dispel some wider myths around ethnic minorities and their connection to the natural world.

“There has been research done in temperate places that suggests that non-white people don’t have as strong a connection to urban trees,” said Trevor Caughlin, assistant professor at Boise State University.

The report disputes this assumption, noting that recent emigrant ethnic groups from the tropics face a “climate barrier” when it comes to transferring culturally important tree species to their adopted homes in temperate regions. “I think that’s a useful finding,” said Caughlin, “because maybe it suggests that there is some education effort or something that can be done to improve the links that people feel to nature in new places.”

The report notes that concerns about the high proportion of exotic species in urban flora can be found in other studies on urban forests in South America. However, it challenges this perspective by highlighting the cultural value of trees – an aspect even some of its own authors didn’t fully appreciate before.

“This paper really made me re-evaluate my perspective on invasive tree species,” said Caughlin, “because I think there are non-native tree species in Georgetown that still have enormous value because they provide a link between the people that live in Georgetown now and their ancestral practices in India and Africa.”

Exploring attitudes towards trees among people in Georgetown, therefore, could inform urban planning not only in Guyana’s capital and other tropical cities, but urban centers in temperate countries that have diverse populations.

Myths and mantras

In Guyana, trees have an important role not just in terms of culture but in religion and worship. Comfa (or komfa), for example – a folk religion that draws on the various beliefs of the ancestors who came to Guyana – makes use of the calabash in its rituals. The drums used in its ceremonies would also be carved from trees.

Drums are important in Hindu rituals too. In fact, Mayor Narine (who also happens to be a pandit, or Hindu priest) said that there are many sacred plants and trees to be found right in the capital. “Peepal tree is very important,” Narine said. “We [Hindus] worship in mandirs, but when my foreparents came to Guyana we didn’t had those huge nice building in those days, so they used to do it under peepal tree.”

The leaves of the mango tree are also used in religious functions. “There are sacred mantras you recite to perform the ceremony with these leaves,” Narine explained. He added that Hindus believe trees have a certain energy. “When you look at tree it’s just like a human being, it’s a living entity.” Destroying a tree, he said, has the impact of destroying a human being.

Trees also play an important role in maintaining intangible cultural heritage such as oral stories, legends and myths. In the 1990s, local author Barry Braithwaite published a graphic novel entitled “The Legend of the Silk Cotton Tree.” It tells the story of a pregnant woman called Elsa who falls asleep by a silk cotton tree and dreams that she should carry out a ritual by the tree. It turns out that the spirit dwelling inside the tree is actually trying to inhabit the child.

The silk cotton tree (or “kumaka” tree in the indigenous Makushi language) holds a fascination and spiritual importance for many Guyanese.

“The silk cotton tree was sacred to both African and Amerindian before colonial times,” explained Barrington. “It has the same symbolic meaning of spiritual relevance. I think the Caribs [one of the nine indigenous peoples of Guyana] also felt that tribesmen re-ascend to the heavens through this tree – this tree is a kind of a portal with them.”

It’s even said to have mind-altering properties. “An old man once told me that when it blooms he believes that there is a hallucinogenic aspect to its seed, but I keep far from that!”

Over the years, the different traditional beliefs have been replaced by the story of Dutch money being buried under tree. “This has to do with a famous trial in 1950 where a woman was hung for sacrificing a child to Dutch spirits for money,” explained the author.

Another legend has it that the Dutch would bury their treasure under silk cotton trees, then kill slaves and bury them with the hoard so their spirits would protect it.

A fear remains among some Guyanese (particularly older generations) that cutting down a silk cotton tree will release a vengeful spirit. Although some have been felled, others have been carefully preserved. That is why in Perseverance, Mahaicony, along the east coast of Guyana, a silk cotton tree sits in the middle of the road built around it.

Also culturally important is the cork tree, said Brathwaite, which is home to the “jumbie bird” (Crotophaga ani) – a kind of messenger between worlds. “That lore is still active but the preservation of those things kind of re-iterates a relationship with the soil you inhabit.”

He is frustrated by what he sees as a lack of recognition of the cultural importance of trees in Georgetown. “When it comes to the management of the city council, they are clueless to the aesthetic that has to do with lore about these things.”

Changing climate

Despite their cultural, environmental and nutritional importance, trees in Georgetown are under threat. And not just in the backyards of residents.

Some colonial-era trees (dating back over 100 years) have simply fallen down, due to climate change and, some say, poor management.

“Over the last 20 years we’ve been losing them faster than we can plant and grow them,” said a worried Peggy Chin from the small plant store she operates next to Georgetown’s Chinese Association.

“It’s a sore point for me. I’ve spoke to the mayor and city council and I’m getting no headway about starting a tree-planting exercise and [pruning] the trees properly. Presently they’re using men going up in the tree with cutlass instead of getting a long arm or a cherry picker – least to say they’re not experienced in trimming the trees because they’re butchering them.”

Since taking office in 2015, the President of Guyana has designated October the month for tree planting and the emphasis is on fruit trees, said Chin, so people will have some fruit to eat. She says that isn’t enough. “The streets and the avenues still need the ornamental trees: for one they protect us, they give us shade. For two – the most important factor – they absorb all the carbon dioxide and they purify the air that we breathe in.”

While Chin waits for the mayor and city council to take her up on her offer of pruning classes, she shares her expertise with Georgetown’s population through her weekly gardening column in a local newspaper. “I always give the description – the origin of the tree, the common name and the botanical name – so people accessing Stabroek News every week would get a little history on all the trees and plants that’s growing in Guyana.”

The authors of the report, meanwhile, hope that their data and conclusions will help the city’s urban planners to not only increase tree cover but to select the right trees for the right locations in order to meet the needs of residents and their environment.

This fits in neatly with the government’s plans for a greener country – what they call their Green State Development Strategy. But balancing this with a growing economy (not to mention becoming an oil nation) will be tricky.

If Guyana wants to achieve a green state by 2040, lead author Hunte said, focused action is needed “to shape our cities by having the trees alleviate some of the impacts of climate change.”

Supervisor Thomas, who has overseen the Botanical Gardens for eight years, has noted the impact of changes in weather patterns. “We have increased rainfall now,” he said. This means more erosion. “We’re losing a lot of trees that we had in the past. At one time we had over 100 species of palms here in the gardens.”

Given the increased rainfall, which can cause the gardens to flood, Thomas says Eucalyptus trees are important because of their ability to absorb water.

The garden is helping to promote biodiversity through a variety of terrains within its own gates: some manicured, some wetland, some savannah style. “To the average person just seeing the overgrown trees at the back they say ‘Oh it’s bush’ but it’s more than that,” Thomas said. “It’s home to a lot of different species of birds, monkeys, all types of things that you wouldn’t see just by walking through – you have to actually go in to know what is going on there.”

Back in her kitchen after another busy lunch rush, Dabie muses on what her favorite tree would be. She settles on the coconut.

“It just has so many uses,” she says. “We use the branches to make pointer brooms that I still use to sweep the house and yard with. I love cooking with the milk in curries and cook-up especially, it adds to the flavor. The water is very nutritious. I’m anemic so it gives me the boost I need.” She even makes her own coconut oil for her hair and skin, and cites various crafts made by local artisans from parts of the shell.

It seems urban Guyanese are not about to forget the connection to their trees just yet.

About the Author: Carinya Sharples is a Guyanese freelance journalist, writer, teacher and editor currently pursuing a Masters in Creative Writing and Education at Goldsmiths, University of London. She writes about the environment, culture, arts, social equality and grassroots projects for BBC Latin America & Caribbean, Mongabay, Gal-Dem and others. She has produce radio pieces for BBC World Service andtaught communications at the University of Guyana as a part-time lecturer. Her work ranged from managing the BBC’s Peabody Award-winningEbola WhatsApp/Facebook services, to writing about a cafe for recovering addicts in London, to visiting NASA’s Johnson Space Center for Channel 4’s BAFTA award-winning series Live from Space.